The robots are coming – for jobs. This is the plain, cold, hard fact we now face as we head towards the third decade of the 21st Century. The technology-driven world in which we now live is one filled with promise – cars that drive themselves, algorithms that respond to customer service inquiries, automated business intelligence on tap. Yet, this brave new world is also filled with challenges. For even as AI and automation increase productivity and improve our lives, their widespread adoption means that many work activities humans currently perform will soon be displaced – if they haven’t been already. What this doesn’t mean, however, is that there will be a shortage of jobs in the future. In fact, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF), AI will create more jobs than it destroys – by 2022, though 75 million jobs are expected to be displaced by automation, 133 million new ones will emerge. Nonetheless, if we don’t take the right steps to educate and (re)train the workforce, what this massive revolution of the working world does mean is that there will be a serious shortage of talent with the necessary AI skills to fill the new jobs that are created.

Table of Contents

ToggleIn the next three years, as many as 120 million workers in the world’s twelve largest economies (including 11.5 million in the US) will need to be retrained or reskilled as a result of AI and intelligent automation, according to a new IBM Institute for Business Value study. Additionally, almost two-thirds of today’s students will end up working in jobs that do not yet exist. Not only does this AI skills gap impact prospects for individuals, but it also has a systemic effect on the ability of companies, industries, governments, and communities to realize the full potential of the world’s digital transformation. The challenge we now face is how to empower the workforce and – most importantly – the youth of today for the jobs of tomorrow.

The AI Talent Shortage

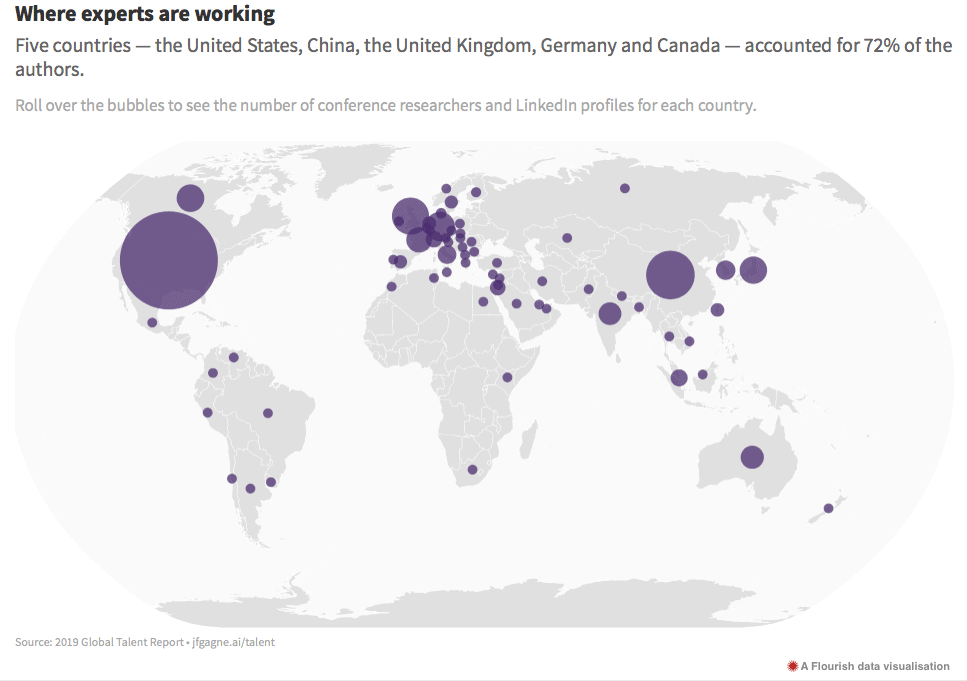

The extent of the global AI skills shortage is laid bare in the Global AI Talent Report 2019, published on the blog of software entrepreneur and CEO of Element AI, Jean-Francois Gagne, and based on analysis of PhD-qualified authors publishing academic papers at world-leading AI conferences. The report identifies that there are 22,400 top AI academics around the world as of 2018. In addition, via a complementary survey of LinkedIn profiles, the report also finds that there is a total of 36,524 people who qualify as self-reported AI specialists, according to the authors’ search criteria. Though these figures represent significant increases over previous studies (up 19% over last year in the case of qualified AI specialists, and up 66% in the case of self-reported AI expertise on LinkedIn), given just how prolific AI and machine learning technologies are becoming, the number of AI experts around the world today remains alarmingly small.

It should be noted here that Gagne’s study sits amongst other, much broader reports, such as the oft-quoted “Global AI Talent White Paper” by Chinese tech giant Tencent, which indicated that there were 300,000 AI researchers and practitioners worldwide in 2017. The number far exceeds the findings in Gagne’s report primarily because it includes entire technical teams that work in AI, and not just the specially-trained AI experts – i.e., those who are well-versed enough in the technology and with the specialist AI skills required to lead teams taking AI from research to application. However, no matter which figure you prefer, the fact remains that there are mere thousands of engineers with AI skills worldwide – but millions are needed.

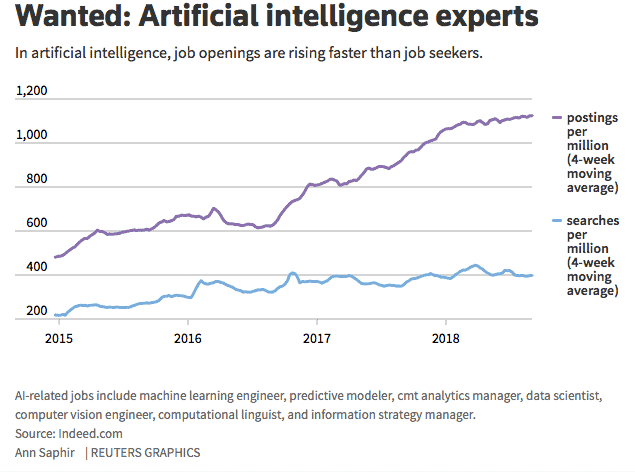

As such, AI remains a “job seeker’s market,” Gagne’s report concludes, with there being no shortage of opportunities in companies developing technology for things like self-driving cars, smart home products, digital assistants, and much more besides. Recent data from Indeed.com reveals that AI job postings rose 29.1% over the last year – and yet, no doubt due to the AI skills gap, searches for AI-related jobs decreased by 14.5% over the same period.

“For example,” say Indeed’s analytics team, “consider data scientists, whose job is to take raw data and apply programming, visualizations and statistical modeling to extract actionable insights for organizations. Given that data is ‘the new oil,’ data scientists are in high demand, and our research shows job postings jumped 31% from 2017 to 2018. During the same period, however, job searches only increased by about 14%.”

The shortage of AI skills is seen as a major barrier to the pace of the technology’s adoption. In fact, a recent poll confirmed that 56% of senior AI professionals believed that a lack of additional, qualified AI workers was the single biggest hurdle to be overcome in terms of achieving the necessary level of AI implementation across business operations. As an example, Element AI last year estimated that there were fewer than 10,000 people around the world who have the necessary skills to create fully-functional machine learning systems. In short, though huge demand already exists for AI skills, the shortage of talent is slowing down hiring – and without new AI hires, organizations simply cannot press forward with their AI strategies.

The AI Talent Pool

The AI talent pool is indeed shallow – so where in the world are the few individuals who possess AI skills working today? Well, according to the Global AI Talent Report 2019, the countries that are most committed to training top AI experts are also leading employment – and the US is ahead of them all.

Among the authors publishing academic papers at world-leading AI conferences, more than 44% earned their Ph.D. in the United States. Authors trained in China accounted for almost 11% overall, followed by the UK (6%), Germany (5%), and Canada, France and Japan (4% each).

(Image source: jfgagne.ai)

A similar geographical distribution characterized the study’s employment data. American employers attract the lion’s share of top AI talent – 46% worked for a US-based employer. China took the second spot on the list, accounting for 11% of employment, followed by the UK at 7%. Canada, Germany, and Japan each accounted for 4%. Overall, five countries – the US, China, the UK, Germany, and Canada – accounted for 72% of the authors.

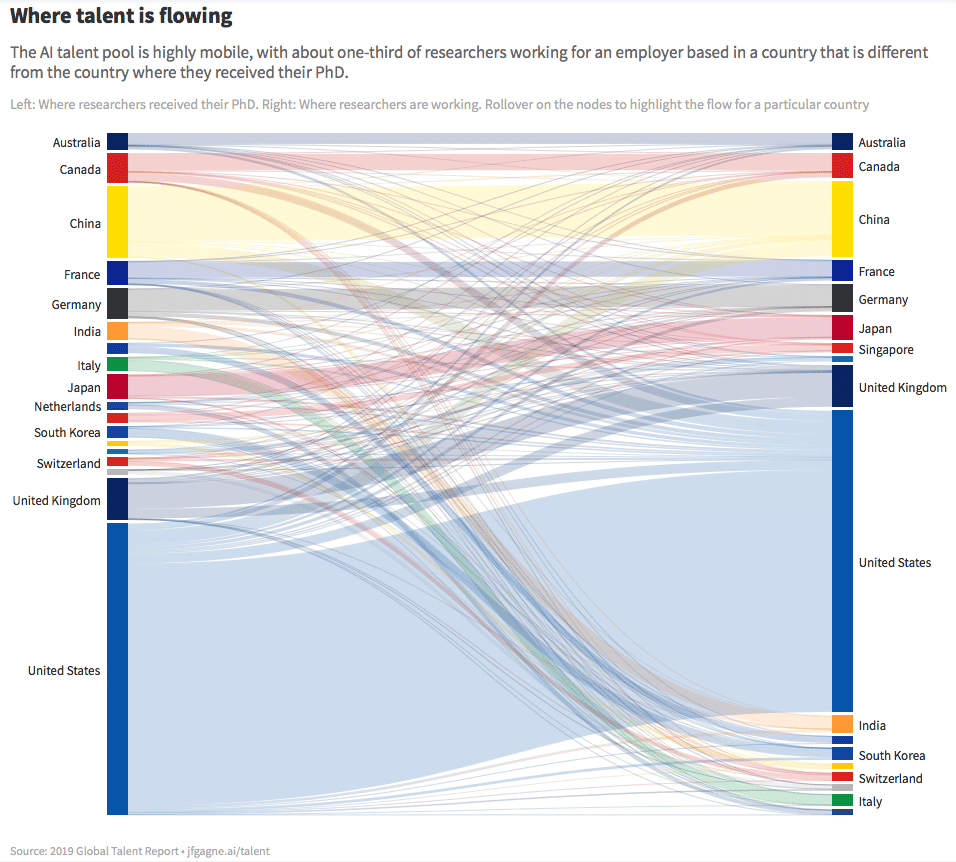

But where are these highly-trained AI specialists employed? Universities, mostly. 77% were found to work in academia, with less than one quarter (23%) working in industry – though not all work for an employer based in the same country where they received their training. In fact, overall, it was found that almost a third (27%) of top AI talent were working in a different country. The study’s authors note that though the global map of these movements is complex and the story behind each move inevitably unique and personal, the data nonetheless allows for some observations about the flow of AI skills across national borders.

First, certain countries are particularly attractive for AI researchers. According to the survey, US-based employers had the highest chance of attracting talent trained abroad. China was the second-most likely country to draw researchers who had received their PhDs in another country, bringing in almost a quarter of the total number of foreign researchers the US was able to attract. The report presumes that several different factors could be contributing to this observation, including the availability of jobs in each country.

(Image source: jfgagne.ai)

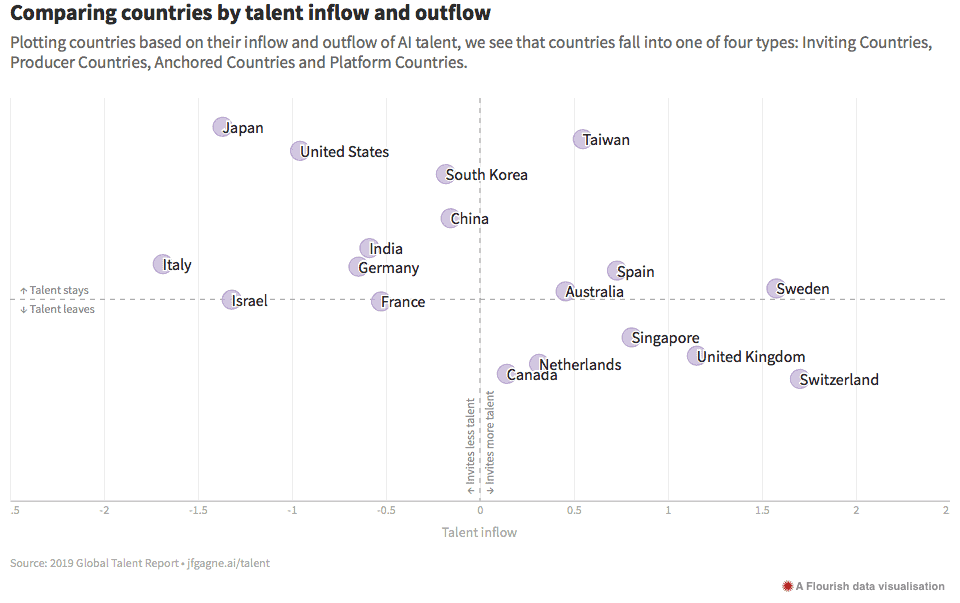

Comparing the talent inflow and outflow in each country as a percentage of the country’s overall talent pool, Gagne et al categorize each country as follows: Inviting Countries, Producer Countries, Anchored Countries, and Platform Countries.

Australia, Spain, Sweden and Taiwan all saw more inflow and less outflow – as a proportion of the country’s overall talent pool – than average. This means that these countries are relatively more successful at both retaining the talent they’ve trained at home and attracting talent from other ecosystems. These are “Inviting Countries”. By contrast, France and Israel are considered “Producer Countries”, because they saw less inflow and more outflow than average.

The US had both less talent inflow and less talent outflow than average. This does not reflect the size of its talent pool, however – in absolute numbers, the United States remains the leading global talent magnet. Rather, it signals the relative stability of its talent pool – and the same pattern was observed in China, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. These ecosystems are considered “Anchored Countries”.

Finally, several countries – including Canada, the Netherlands, Singapore, Switzerland, and the UK – saw both more inflow and more outflow than average. These countries are succeeding at attracting AI skills from abroad, while also seeing more post-graduate movement than average. These ecosystems are considered “Platform Countries”.

(Image source: jfgagne.ai)

The data also shed light on some notable talent exchanges between certain countries. For example, there was a particularly strong exchange between China and the US – around 500 of the 22,400 researchers in the data set received their PhD in China and then went on to work for a US employer, with around 500 more traveling in the opposite direction. A similar phenomenon was observed between the US and the UK, where about 325 AI experts moved to the UK after receiving training in the US, with roughly the same number of UK-trained experts going on to work for a US-based employer.

Women Continue to Be Underrepresented

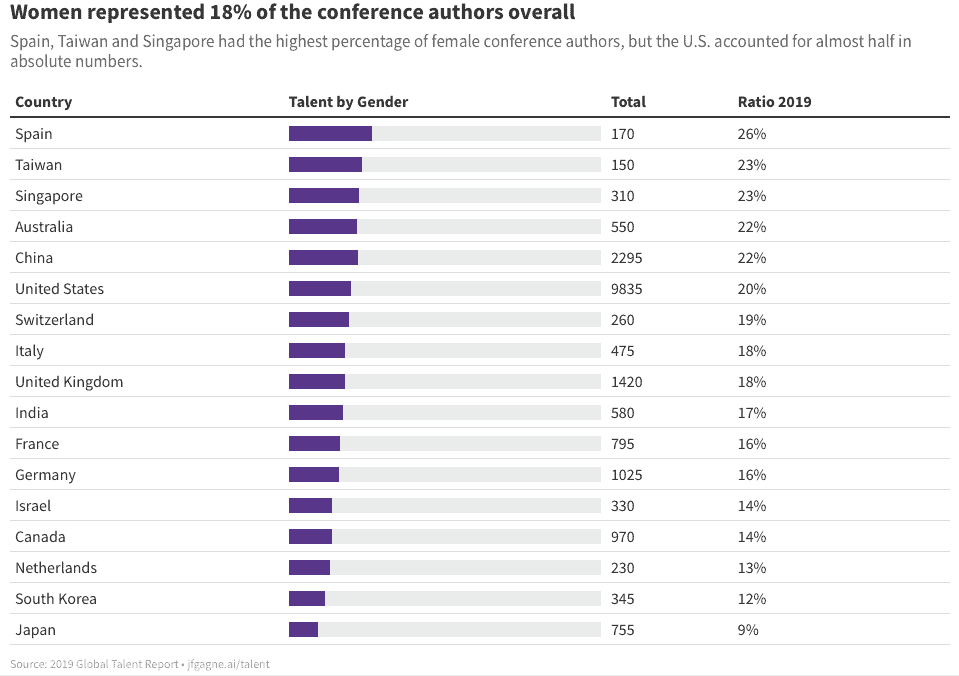

Gagne et al also analyzed the global talent pool to try and see what proportion of researchers with top AI skills were women. The review reveals that the field is still miles away from reaching anything close to a gender balance.

In last year’s survey, it was found that just 12% of PhD-qualified authors publishing academic papers at world-leading AI conferences were women. This year, though the figure rose to 18%, it remains woefully imbalanced – and the disparity exists in both industry and academia. The data indicates that 19% of the conference authors who were in academia were women versus 16% in industry.

As noted in the report, equality in the field of AI is vital to the technology’s ethical success, given the potential for society-wide impact. Professor Joelle Pineau, who heads the Facebook AI Research lab in Montreal, is quoted: “We have more of a scientific responsibility to act than other fields because we’re developing technology that affects a large proportion of the population,” she said.

(Image source: jfgagne.ai)

It was also found that, according the AI Index 2018 Report, published by Stanford University, women are also underrepresented in undergraduate AI and machine learning courses. Stanford’s 2017 “Intro to AI” course was 74% male, and UC Berkeley’s course was 73% male, according to the report. An even lower percentage of women enrolled in the universities’ “Intro to Machine Learning” courses, with men accounting for 76% of the students in the Stanford course and 79% of the students in the UC Berkeley course. The same report found that in the US, the majority of applicants (71%) for AI jobs are men.

Contributing Factors to the AI Skills Shortage

Today, practically every company is considering how artificial intelligence can positively impact their business. According to the 2019 AI Skills Gap report from SnapLogic, 93% of US and UK organizations consider AI and machine learning to be a top business priority, and have various projects planned or already in production.

(Image source: snaplogic.com)

As demand – and C-suite excitement – for various AI applications builds, demand for AI professionals is ballooning in kind. However, academic and training programs simply can’t keep up with the pace of innovation and new discoveries in AI. AI workers need both official training and on-the-job experience – and, as clearly evidenced by Gagne’s report, there simply aren’t enough experienced AI professionals to step into leadership roles to provide it, and the talent that does exist remains internationally scattered.

(Image source: reuters.com)

Learning pathways and career strategies are also unclear – especially, as the data reveals, for women. Interest in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects amongst younger generations remains low – again, especially amongst females – and there are large achievement gaps.

Universities are trying to keep up. According to Reuters, applicants to study AI in UC Berkeley’s electrical engineering and computer sciences doctoral program numbered 341 a decade ago, but had surged to 2,700 by last year. The University of Illinois also recently tripled its enrollment cap on the school’s “Intro to AI” course to 300 – the extra 200 seats were filled within 24 hours. Last fall, Carnegie Mellon University began offering the nation’s first undergraduate degree in artificial intelligence. “We feel strongly that the demand is there,” said Reid Simmons, who directs CMU’s new program. “And we are trying to supply the students to fill that demand.”

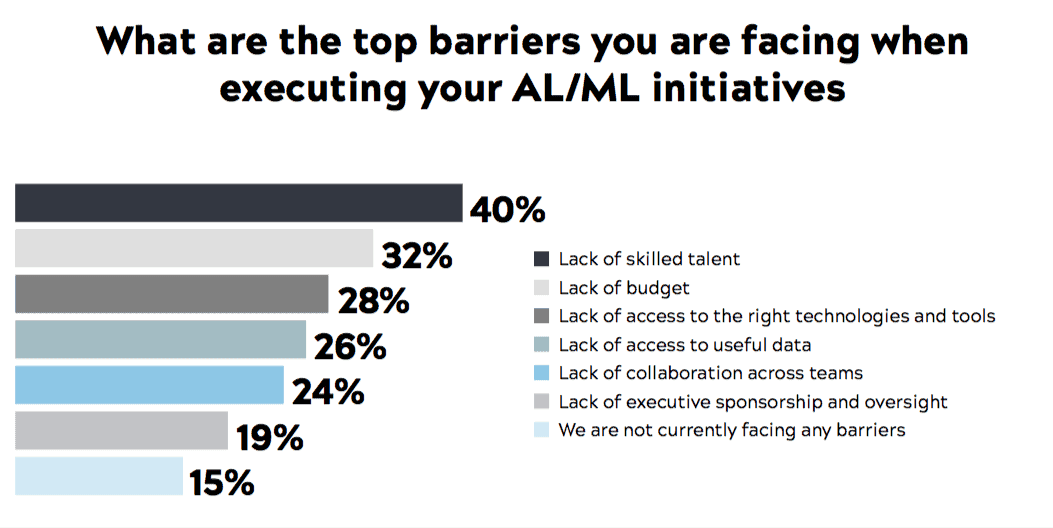

Still, even as schools and universities across the country add new classes and courses, a fix for the AI skills gap is yet some years away – and it’s impeding growth at many companies. The 2018 “How Companies Are Putting AI to Work Through Deep Learning” survey from O’Reilly reveals that the AI skills gap is the largest barrier to AI adoption – results that are reflected in the SnapLogic survey, which found that 51% of IT leaders say they don’t have the right mix of AI skills in-house to bring their strategies to life. In fact, a lack of skilled talent was cited as the number one barrier to progressing artificial intelligence initiatives by 40% of respondents.

(Image source: snaplogic.com)

In short, the AI skills gap has emerged primarily because of the quickening pace of digitalization in the workplace, combined with an education system that hasn’t produced workers with the skills required to meet the demands of the modern world.

Closing the AI Skills Gap

One of the ways to address the AI skills gap is of course to increase resources for digital, math and technical education, as many universities around the US are starting to do, and as the UK Government announced in its 2017 Industrial Strategy white paper. However, while skills acquisition for younger generations will help in the future, simply driving more students into STEM and computer science subjects will not solve the issue either now or in the future – the number of computer science graduates in the UK would need to increase ten-fold to meet 2022 demand.

Another avenue is for companies themselves to address the problem head-on and invest more in reskilling their workforces – but they need to do so quickly. The World Economic Forum estimates that more than half (54%) of all employees around the world will require significant reskilling by 2022, though the AI skills gap is even more pronounced in some regions. The WEF highlights European Commission figures, for instance, which indicate that around 37% of workers in Europe don’t have even basic digital skills, let alone the more advanced and specialized AI skills companies need to successfully adopt new technologies.

Some large firms are already investing heavily in upskilling their workforce. Amazon, for instance, recently announced a plan to invest more than $700 million to retrain its US workers, which will enable many to move into skilled technical roles in the company’s corporate offices and tech hubs. In particular, Amazon is focusing on job roles like data mapping specialist, data scientist and business analyst – all of which involve and require AI skills.

Booz Allen Hamilton Inc. – which provides analysts and systems support to the National Security Agency, the Pentagon, and other US intelligence bodies – also knows the struggle of finding good data scientists, and so in 2017 launched a drive to add 5,000 workers with data analysis, science and engineering skills. However, being aware of the talent shortfall, the company knew that it couldn’t fill all these positions from the outside, so it decided to upskill from within. By early 2019, Booz Allen was providing data analytics and visualization training to about 1,000 employees already on the payroll, reports The Wall Street Journal. “Our business model is dependent on talented people,” said Lloyd Howell, the company’s CFO and Treasurer. “Training comes at a cost, and it certainly has increased over the last five years. But this is an important area for us to keep pace in.”

Indeed, it is – as Johnny C. Taylor, Jr., President and CEO for the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), puts it: “We are past the point where this is a choice. We need to do this; we need to invest in employee training.”

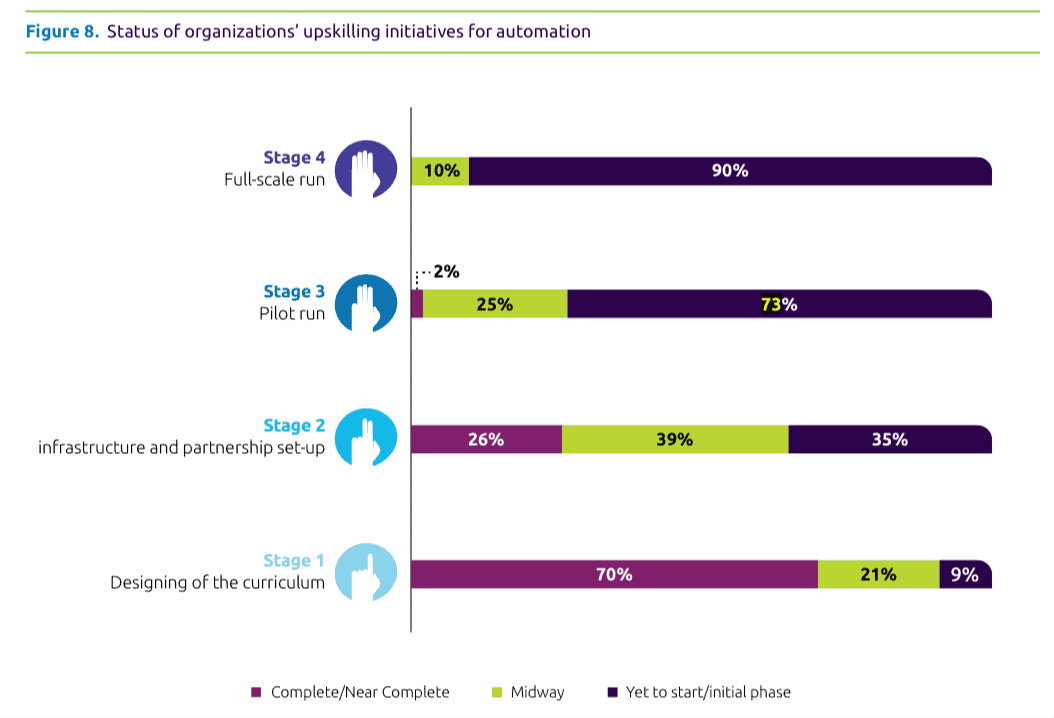

However, many more companies need to follow in Amazon’s and Booz Allen’s footsteps for demands to be met. According to a recent Capgemini report – “Upskilling Your People for the Age of the Machine” – despite the urgent need for action, nearly three-quarters (73%) of organizations have not even begun an upskilling pilot program to adapt their workforces, and only 16% have plans to upskill their current workforce as a primary response to the crisis.

(Image source: capgemini.com)

The Agorize AI for Societal Impact Challenge

There are, of course, other ways for companies to source AI skills. Though the Global AI Talent Report focusses primarily on the number of AI academics currently available to potential employers, the fact is that a college degree is no longer a prerequisite for a career in AI. Companies can develop their own courseware for reskilling and upskilling their employees – several online learning platforms such as Coursera, Udacity and Udemy, for instance, have promised to help businesses stay ahead of digital disruption by offering courses in data science, machine learning and AI. But there are thousands if not millions of individuals around the world who are also taking the initiative to educate themselves. The challenge, however, is connecting these self-trained individuals with the organizations that need them – something that leading online platform for open innovation challenges Agorize is set up to achieve.

(Imager source: agorize.com)

Agorize consists of a pool of 5 million innovators worldwide, including 3 million students, 1 million developers, 300k startups, and 800k employees. The goal is to connect businesses with these innovators through open innovation challenges – the most recent of which is the AI for Societal Impact Challenge, developed in partnership with Microsoft, the Information Technology Association of Canada (ITAC), and the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), and led by Aurelie Wen, Managing Partner at Agorize, and Founder of the company’s North American Office.

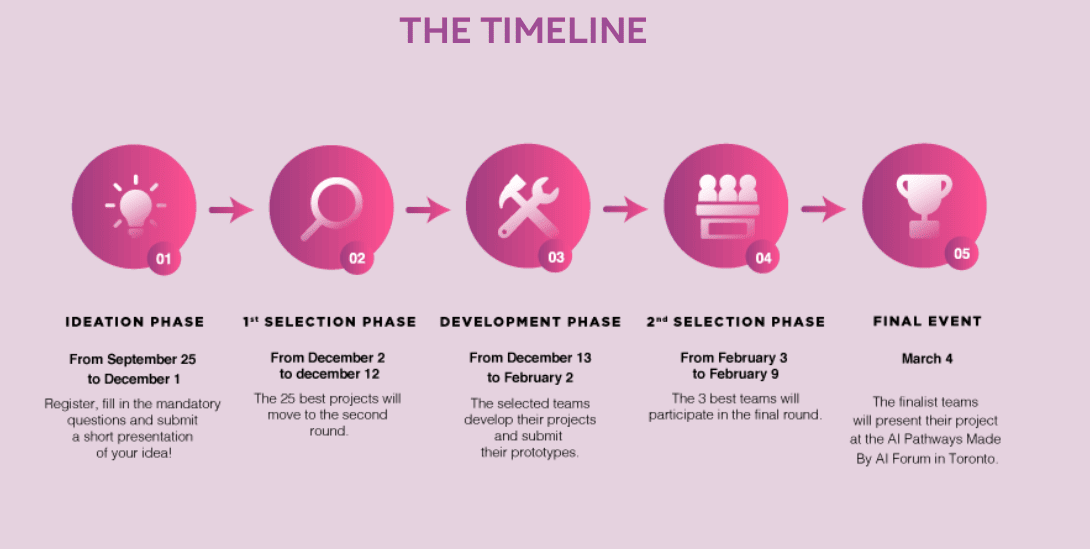

The new challenge is open to all post-secondary students from Canada. The mission is to create or join a team of two to four people and develop a project that will make a societal difference by leveraging Microsoft Azure and Microsoft Learning to further develop or explore new AI skills. All ideas must be based on one of three given topics – Sustainable Future, Future of Work & Education, or Social Equality.

(Image source: agorize.com)

Participants can take advantage of $100 worth of free Microsoft Azure credits, and are encouraged to explore Microsoft’s Machine Learning Modules to learn new AI skills and spark new ideas for the challenge. Ideas are welcomed from anyone – no previous technical skills are required – and participants can even continue working on their ideas after the challenge, as they will keep the intellectual property rights for everything they develop. Expert mentoring is provided, as well as a range of resources to help participants get inspired, learn new AI skills step-by-step, and find the right tools to start an AI project.

“As the world continues to be transformed by technology, everyone should have access to the tools and digital skills critical for their future success,” said Kevin Peesker, President of Microsoft Canada. “At Microsoft, we firmly believe that creating a culture in which technology blends with human potential is the key to thriving in this new cloud economy and are pleased to partner with ITAC and RBC to help upskill Canadians, particularly those in underserved communities.”

RBC’s involvement is part of its Future Launch project – a 10-year, $500 million commitment to help Canadian youth prepare for the jobs of tomorrow. The Future Launch program is designed to increase access to skills development, networking opportunities and work experience to help prepare young people in Canada prepare for what’s next in the world of work.

“As digital and machine technology advances, the next generation of Canadians will need to be more adaptive, creative and collaborative, adding and refining skills to keep pace with a world of work undergoing profound change,” said Valerie Chort, Vice President of Corporate Citizenship at RBC. “That’s what RBC Future Launch is all about, and through our partnership with ITAC and other organizations, we hope to enable young people to identify, articulate and build their skills – and help young Canadians develop them.”

As the leading platform for hackathons and open innovation challenges, Agorize and the partners it works with has helped more than 200 major organizations in North America, Europe and Asia – Including Deloitte, Google, Tinder, HSBC, Schneider Electric, the US Department for Education, and Automation Anywhere – connect with millions of innovators and bring new solutions to life. In addition, Wen and her team have helped more than 60,000 students and innovators launch their startup and find jobs at companies, such as TD National Bank of Canada, Desjardins, Aviva, Radio-Canada, L’Oréal, PepsiCo, and more.

“Large communities and potential clients are interested in the value of our community, first, but also in the platform itself,” said Wen. “From all the platforms that exist in the country, there is no such platform that can manage a hackathon online as well as our platform.”

The ideation phase for the AI for Societal Impact Challenge is open now until December 1 – a fantastic opportunity for students and individuals to start honing and expanding their AI skills, connect with businesses in need of them, and expand their networks.

Final Thoughts

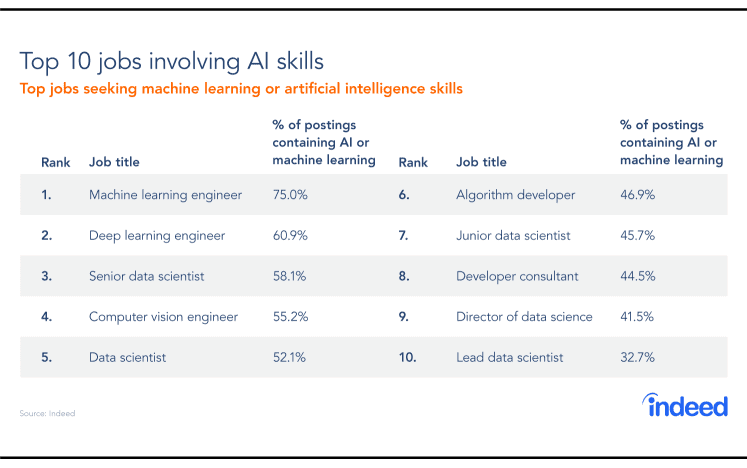

The AI skills gap amounts to nothing short of a crisis that the business world needs to address urgently. The talent pool is alarmingly shallow, with more jobs available than the number of qualified individuals to fill them. Many countries are feeling the strain of the AI skills shortage, and education systems have been too slow to keep up. According to job postings on Indeed, the top ten AI skills in demand from companies today are as follows:

(Image source: blog.indeed.com)

With so many roles unfilled, the AI skills shortage must be addressed before companies can even begin to hope that they will reach the level of AI integration needed to propel their businesses forward. The time is now for organizations to start upskilling their workforces to prepare for future disruptions and innovations – but at present, many are being too slow to do so.

The inaction is difficult to fathom, given the urgent need to develop a proactive response to the AI skills gap – and businesses that don’t take action now to tackle the problem will undoubtedly be left behind.

Clearly, there’s no one way to solve the AI skills crisis. At present, however, AI remains a job-seeker’s market, and in lieu of more companies taking the appropriate initiatives, individuals seeking to upskill themselves or pursue a career in AI can do so online through programs like the AI for Societal Impact Challenge, and the many learning opportunities that its founding partners are making available. While there is no easy solution, companies who plan to use AI today or in the future need to consider now how they will tackle the AI skills shortage – and self-motivated individuals should take up the challenges and access the resources being offered to get out ahead.

AI Skills Shortage

If we don’t take the right steps to educate and (re)train the workforce, what this massive revolution of the working world does mean is that there will be a serious shortage of talent with the necessary AI skills to fill the new jobs that are created. In the next three years, as many as 120 million workers in the world’s twelve largest economies (including 11.5 million in the US) will need to be retrained or reskilled as a result of AI and intelligent automation, according to a new IBM Institute for Business Value study. Additionally, almost two-thirds of today’s students will end up working in jobs that do not yet exist. The shortage of AI skills is seen as a major barrier to the pace of the technology’s adoption. In fact, a recent poll confirmed that 56% of senior AI professionals believed that a lack of additional, qualified AI workers was the single biggest hurdle to be overcome in terms of achieving the necessary level of AI implementation across business operations.